I'd like to push back on something.

For a very long time – and most recently in an article by Tom Van Winkle last month – lots of GMs and RPG writers have recommended that when a player character's attempt at a task results in a very unlikely success or failure, it should be treated as 'discovering something new about' (i.e., changing the GM's mental model of) the game world.

When the task resolution mechanic reports a surprising success, the task was actually much easier than it seemed (for some reason that the GM comes up with). A surprising failure likewise means something in the world made the task much more difficult.

The lichvanwinkle article aptly sums the idea up as 'The "failure" [or success] with the dice gives an opportunity to define the world in ways that are not just about the character.'

(I like pretty much all of Van Winkle's writing;

this is just one of those cases where you nod along appreciatively in silence

for years and then only bother to pipe up when you

disagree.)

To extend two of his examples:

Surprisingly, the accomplished locksmith fails to pick the simple lock on the store. So...

- The lock mechanism must be broken, rusted solid, or jammed shut

- The lock does open, but it turns out the door is stuck or barred

- As the locksmith is just starting, she hears guards approaching, so can't complete the covert work

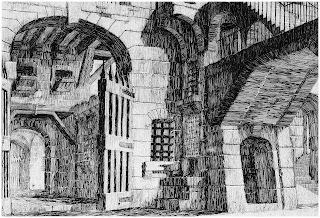

Surprisingly, the puny wizard manages to bend the metal bars in the prison window. So...

- The metal bars are rusted completely through, and give way.

- The bars were only an illusion all along!

- The bars are solid, but the wizard finds the stone is old and degraded – he can just chip it away and pull the bars out.

(Note that the probability and mechanic for the unexpected success or failure doesn't matter. It could be 'natural 1 = automatic failure' or 'exploding dice leads to preposterous successes' or 'disregarding the rules, this particular GM always tweaks the Target Number so any PC can always succeed or fail'.)

Now, I usually like the idea of 'overloading' dice with extra meaning. Reducing the number of dice rolls is almost always a great design goal.

So why not here?

This is one of those ideas that's really mostly innocuous, but is so widespread that I want to push back on it for fear that it will become the status quo. "An unlikely dice result changes what's in the world" is definitely not a panacea solution, and you may find that it can create some problems of its own.

And what it boils down is that overloading the action-resolution dice in this particular way thwarts a really fundamental, really effective TTRPG loop:

(ii) Whenever a player character's passive senses would tell them something remotely meaningful about the world-state, the GM gives the player that information.

(iii) A player can have their PC investigate (interact with) their environment to get further information about the world-state.

(iv) The difficulty of a task is determined entirely by the world-state (including as it does all PCs and NPCs, secrets and fixtures, physics and metaphysical forces, gods and demons, self-inserts and metanarrative powers, etc).

(v) Players can estimate the difficulty of a task by how much they have learned via (ii) and (iii); they can attempt to reduce risk by doing more of (iii) and the GM can make the game require less back-and-forth by doing more of (ii).

(vi) Players have a single 'game action': declare their intention to attempt some task which they describe.

(vii) When a player uses their game action, the GM: first checks whether anything should happen before or simultaneously by consulting the world-state and/or the other players, then checks they and the player are envisaging the same thing with regard to the player action, then considers difficulty via (iv), then (only if the task could either succeed or fail) determines which game mechanics to use to resolve it, then resolves it, then narrates the attempt and its outcome via (ii).

Notice how many of those steps are disrupted if the action-resolution dice can make a retroactive change to the world!

An idea in conflict with TTRPG best practises

More specifically, the idea that 'unlikely dice results change the world' conflicts with six important bits of TTRPG advice which are ubiquitous in modern discourse:

1. Don't make the characters do anything the player didn't try (outside of minor, obvious, safe, unstated things; always assume a character is competent). An 'unlikely dice result' should not change what a character was doing.

- The outcome of the action "I try to pick the lock" can't be "you were so overconfident that you tried to pick the simple lock without torsioning the keyway, so you failed". The player didn't attempt that and the character shouldn't be incompetent.

- Likewise the outcome of the action "I try to bend the prison bars" can't be "you chip away a bunch of what turns out to be ancient, crumbling stone and pull the bars out instead". We can easily imagine cases where the player would decide not to take the alternate option. (And if you stop and give them the "new information", they're now deciding based on information that was first created and then discovered by the outcome of a "use crowbar to bend metal bars" resolution mechanism which didn't do anything. Weird.)

- So this substantially constrains your options for retrofitting the world to an unlikely dice result.

2. Don't roll if the outcome doesn't matter. If the outcome of the roll is so surprising that it's incompatible with your vision of the world as GM, to the extent that you have to change your mental model of the world-state in order to keep it consistent, it means you should never have had the player roll in the first place! You should have just said "yes" or "no"! (If the game procedures told you to, it may also mean that those procedures are bad, but that's a different matter). If an expert lockpicker encounters a simple (functioning) lock, and has time and tools and use of her hands, then anything short of a lightning bolt from above means that she opens the lock. There should not be a flat 5% chance that she just "can't". This is true in the real world and in any game that has verisimilitude.

(Rambling aside: Breaking a pick or torsion tool in the lock is rare, at least for someone who knows how to use them. Even if you ascribe that fact to the wonders of modern metallurgy, older locks tend to have larger keyways, so older lockpicks can probably afford to be thicker to make up for it. And most importantly, note that snapping a tool in a lock will almost certainly not jam the lock, preventing it being opened; a competent locksmith will remove the piece and continue to work.)

3. Decide and envisage the world-state before you determine how to adjudicate an action. Whether you need to use any given rule, or involve dice mechanics at all, depends on what is currently true in the world.

- Just because there's a rule for "falling object damage" doesn't mean you use it if the PCs manage to make the moon fall onto their planet.

- Just because there's a rule for "whether an attack hits" doesn't mean you use it when a PC attacks a paralysed target in an otherwise empty room.

Knowing what's true in the world makes the GM's second-most important job (adjudicating action outcomes) very simple. If you were envisaging the lock as functioning, then don't roll: the locksmith cannot fail. If you were envisaging the lock as rusted solid, then don't roll: the locksmith cannot succeed. If you were envisaging the lock as being complex, or being simple but someone has lovingly filled it with honey, then work out an appropriate Target Number and go to the dice. The 'unlikely dice result changes the world' idea makes all this impossible.

4. Decide and envisage the world-state plus the outcome of an action before you describe an event or outcome. If you already know what's true in the world, and you're only letting dice have a say when success or failure are both possible, then you can go from outcome to description immediately.

If an unlikely dice result can change the world, this is more difficult: You have to leave space for things that even you, the GM, don't know about the world. When the dice give a surprising success or failure, you have to – on the fly – determine a change which is compatible with what the player characters already know and also what the consequences of that change will be and more specifically whether this 'breaks' anything else in the world-state or in the current scenario. And then you have to narrate the action outcome while incorporating how the player characters discover the newly-created information.

5. Players are given key information up front, can get as much descriptive detail as they ask for, and can find out more relevant information by interacting with their environment. But, whoops, now an unlikely dice result can change the world retroactively, so what info can be given out?

The GM's single most important job is providing concise, accurate, memorable, relevant descriptive narrative. You just can't do this if you have to worry about 'saving room for' corner cases. If the prison bars are strong, rust-free, corporeal, and set firmly in strong rock "unless in the future I need them not to be, if the weakling wizard rolls high enough to bend them", you have a big problem which grows bigger with every interaction the player characters have with the bars.

At some point, as more and more 'explanations' of the surprising dice result are ruled out by what the players know about the world, you're left with just two options, both unsatisfying.

- A preposterous deus ex machina ("a sudden earthquake rocks the room just as Feebliander begins to push the bar! The wall caves in!"). Even if you try to disguise its extempore nature, you're likely to get the problem of "We immediately waste a bunch of time and resources investigating what has caused this very unexpected thing which we take to be a big clue about other parts of the game world."

- A fake or fiat perception failure ("I know I said Feebliander thought the bars looked new and sturdy when he spent ten minutes studying them carefully, but as he applies the crowbar, he finds them to give way in a spray of rust.") Many game systems have perception mechanics, including ones that are meant to be passively or automatically applied, in which case as soon as you make surprising dice results retrospectively change the world, you've immediately failed in your job of correctly and impartially applying the rules, by either not invoking them or not taking into account information about the world.

6. Don't let the players think you don't know what's true in the world. This is more important than it sounds, especially for invested, smart, skilled players.

But suppose they notice that a lot of the time when they roll really high or really low, there's a bit of a pause and then the GM tells them their action fails or succeeds because of something they hadn't already known about the world. They're going to lose faith that the GM is thinking about their own world. They'll (accurately) regard that as a troubling sign. They'll start thinking things like "the GM can't have known the lock was completely rusted, because then what would be in the point in making me roll?"

More pragmatically, they're going to start checking for all the little factors – is the lock old, is it rusted, is it gummed or jammed or filled with honey, is the door stuck, is anyone else around – BEFORE attempting to pick the lock, and then what are you going to do when the expert locksmith rolls a 1?

Okay yes but

Most of the rationale for 'unlikely dice result changes the world' was that the GM wants to be surprised sometimes. That's valid, right?

Yes, of course.

- You might be worried about fairness ("otherwise I'm just deciding by fiat that the lock is in good working order").

- You might be aware of your own cognitive blind spots ("otherwise I'll just end up using the normal defaults – normal locks, sturdy bars, guards who can't be bribed, trees with enough branches to climb").

- You might be using a system that's simpler than you'd prefer ("Am I really meant to just make up all the Target Numbers?").

- You might want the PCs to encounter more variety than you're capable of providing ("I'm always thinking about the next encounter, so I never remember to have a more mundane task throw an unexpected boon or bane").

So how can you attain this without overloading the task resolution dice?

I think the answer is: take a more rigorous approach, using a dedicated dice roll. You could do it any number of different ways; the key is to identify early on that there's something with various possible states/aspects/nuances which could change task difficulties, and having identified it, quickly make a dice roll to see what's true in your world. Once you have determined the world-state, all the rest of the GM's job is exactly as easy as it ever was.

The solution

It's one of those things you can learn to do without a formal process, just as an instinctive part of the regular rolling-dice-for-no-apparent reason that you ought to be doing anyway to keep the players alert.

But if I had to encode it as a specific procedure, I'd say:

- Pay attention to cases where you start describing something with an obvious PC interaction, especially where you're likely going to have to later improvise that task's difficulty.

- In such cases, first envisage how the world probably is – the default state of the lock given who bought it and used it and when; the condition of the bars given whether this is a gaol in use or a crumbling ruin; the loyalty of the guards given who hired them to do what; etc.

- Then just roll a dice to see whether it's actually better or worse overall for the PCs, with a 1 being "version of the worst case that's still completely plausible" and a maximum roll being "version of the best case that's still completely plausible", the gradations between being easily decided on the fly. Worse cases make for harder Target Numbers for most approaches to most tasks, and so on. A "middle" result (either of the two numbers around the dice's average, which a GM should know) means "don't change what you first envisioned at all".

Pros:

- This is fast, simple, and easy to remember.

- If you forget to roll, or only remember after the characters have started fiddling around with things, it doesn't matter. You don't need to remember every time, only sometimes.

- You can pick up whichever dice is closest and use it.

- Your expectations about the world as the GM often hold true, and things only deviate from your expectations as far as you'll let them.

- When you 'discover' something new about the world, you get that information before you go to action resolution, available to give to any player who has their character investigate how hard various approaches to the task are going to be.

- You never get weird action results that are borderline- or outright-incompatible with the world you envisioned.

I think this better serves the overall purpose of "freedom in narrating the events in a fantasy game without hesitation or squabbling over rules and rulings. Let the dice serve your narration without requiring your narration to mess with the rules further."

Cons:

- That pesky extra dice roll...

No comments:

Post a Comment