What follows isn't an attempt at a codification or taxonomy or definition. In fact, it deviates from some of the language people use to describe TTRPGs and story(-telling) games.

It's a way of looking at the design space that I've personally found useful, and a sketch of some of the ways people end up arguing at cross-purposes about story.

Story ∈ TTRPG

First, the process of playing a tabletop role-playing game does inevitably create stories: whether you think that's the point of playing or not; whether you think the GM should try to steer it or plan it or not; whether you think there's story from start to finish or only after the fact.

Back in 1987, Gary Gygax advised that

When the principal characters in a story (the campaign) are free-willed and have a multitude of choices regarding how to proceed, it is counterproductive – and, in fact, impossible – to preordain just how the events in the campaign will unfold.

In 2009, the Alexandrian made the firm case most of us are familiar with: don't prep plots.

A plot is the sequence of events in a story.

And the problem with trying to prep a plot for an RPG is that you’re attempting to pre-determine events that have not yet happened. Your gaming session is not a story — it is a happening. It is something about which stories can be told, but in the genesis of the moment it is not a tale being told. It is a fact that is transpiring.

In 2021, the Angry GM noted that

the story—the narrative—is an emergent thing. Your game’s going to have a narrative when it’s done. Like it or not. And people are going to interpret it based on how they think stories work. Players won’t experience the game as it was. They’ll experience it based on their warped perception of it. [...]

Once your game’s done, it’s going to have had a plot. It’s going to have followed a single sequence of events. There’s going to have been a climax. People—even you—will remember that s$&%. You can either use what power you have to steer the game toward the best narrative possible. One that does the things that thirty millenniums of storytelling have taught us make for good stories. Or you can hope and pray that the emergent narrative is accidentally a good one. It’s your call.

And just recently in 2024, Tom van Winkle wrote a superb article about the nuances of all this. If you only have time to read one blog post today, go read that one instead of this.

The assumption seems to be that to create a story, you need a plot in advance. It's important for the entire entry here to understand that that is not true. [...]

What all the "anti-story" gamers have in common today is that they allowed other people to define the term "story" for them as "pre-designed plot," even though that's not what story means.

He analyses "anti-story" gamers, who

have, apparently unwittingly, accepted the false idea that RPGs would need plots designed in advance to have stories in a story-telling game. Their objections are therefore confusing for many people who are aware that they experience stories arising spontaneously in RPGs.

The underlying claim is: playing a tabletop role-playing game is intrinsically a process of telling a story. And yes, in a technical sense, this is absolutely true. In a TTRPG session, real-world people are making deliberate decisions that lead to the details of a fictional universe and events within it being filled in. Therefore, definitionally speaking, the players and GM have collaborated to tell a story.

Tom van Winkle in particular discusses the literature, and what scholars of story and narrative have agreed on, and how that applies.

The problem, though, is that in everyday, natural English for the layperson, the phrase "tell a story" comes with all sorts of baggage that doesn't necessarily apply to TTRPGs.

The phrase is laden with subtle implications in common English:

- Telling a story means the storytellers are doing so with the primary goal of producing a 'good story', or at least are telling a story intentionally

- Telling a story means the storytellers have equal parts, or at least similar amounts of creative control

- Telling a story means the process is done selectively, without random elements

- Telling a story means that core elements of the narrative are planned (at least a little in advance), not suddenly discovered

- Telling a story means that people are making choices in order to further the narrative in a satisfying way, which might not be the 'optimal' or even plausible choices for a particular character

- Telling a story is unregulated by formal mechanics, or at least largely so

None of these are true of TTRPGs in general. They're not even all true simultaneously for most story-telling games!

So telling a novice who's interested in entering the hobby that a TTRPG is necessarily 'about telling a story' is frankly just misleading that person, unless you stop and break down why 'telling a story' doesn't mean most of what they think it means. (And it may lead to further misunderstandings, like when they hear the term 'player agency' and think it means creative agency over the fictive world, and so on...)

...We still have this phrase, 'story game'.

Two axes

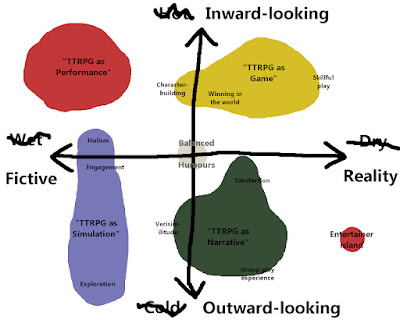

When I think about 'story games' and TTRPGs, I envisage two parallel tracks running left to right.

On the first axis, we have 'rules' to the left and 'freeform' to the right. This axis mostly has to do with the GM, if the game has one.

- A game can be towards the left, 'rules', with lots of rules and processes for decision-making. A game here encourages system mastery for both the GM and the players. It doesn't necessarily imply more control or omniscience for the GM: the game could be heavily reliant on random tables, for instance, or there could be lots of codified rules for how the players get to mess around with the game world directly rather than through their characters.

- A game can be towards the right, 'freeform', taking an open-ended and freeform approach to actual gameplay. In this case the GM is making up a lot as they go along, relying more on the characteristics of the world that have so far been determined than on rules and frameworks provided by the game.

- A game can be somewhere in the middle, with moderate rule support.

On the second axis, we have 'decisions' to the left and 'insertions' to the right. This axis has more to do with the players than the GM.

- A game can be towards the left, 'decisions', where players control their character's mind – the decisions they make – and nothing else. The GM determines what is in the world, controls events and NPCs, and adjudicates PC decision outcomes. (But even the most leftward TTRPGs usually have a carve-out here for character generation, where players get to pick things about their character which the character realistically couldn't have chosen within the world.)

- A game can be towards the right, 'insertions', where players have power over aspects of the game that isn't through their characters. In some situations characters can create, choose, affect, invent, or veto, but in games like this the players have an ability to create, choose, affect, invent, or veto.

- A game can be somewhere in the middle, mixing approaches.

The reason I picture the tracks as parallel is that many games, if you map them onto the axes, make a line that's close to vertical. That is,

- Most, though not all, 'traddish TTRPGs' (games with few to no overt player-available story-telling elements) are also mechanically rigorous. They are towards the left on both axes. In general, the GM has lots of power and mechanical support, and the players will know that most things they choose to do will be covered by rules. Whether those rules are good or bad, players may be uneasy with situations where the GM has to go with their gut over having an 'official' answer. It will be unusual (troubling, even) for a GM to invite a player to fill in gaps in the world or determine action outcomes.

- Most, though not all, 'collaborative story-telling games' (in which players are permitted to insert content directly into the world rather than being restricted to attempts to alter the world with their characters) have relatively few rules and processes. They are towards the right on both axes. In general, there isn't anywhere near as much of an authority disparity between the GM and the players, or there might not be a GM at all. The game rules tend to be 'softer' or 'fuzzier', the players are given more overt license to override or ignore them, and the mechanical framework is usually designed more towards 'crafting a satisfying narrative' than towards 'playing a skill-requiring game' or 'simulating a fictional world'.

I'm personally most interested in the leftward side of both scales. I've designed at least one little game that wanders around the middle of the axes, and have a few others sitting on the project pile, but as a designer and player I mostly lean left, towards 'traddish TTRPGs'.

But I'm also interested, from a design point of view, in the rare oddballs. The really open-ended, rules-light TTRPGs with high GM authority, perhaps like this idea. And the highly constrained, rules-heavy, almost formulaic, versions of story-telling games, with no referee.

Ways of playing

We can map the way people actually play games onto these two tracks, too. As opposed to how games were designed to be played.

The big example here is (as it often is) D&D 5e. The system is to the centre-left on the rules/freeform track: it's crunchy and extensive compared to a lot of indie games, but not as much as previous editions of the same game, or GURPS, or whatever). And it's quite far left on the decisions/insertions track: the official rules only contain (outside character generation) a few optional and tacked-on suggestions about direct player control over the world.

Interestingly, this isn't always borne out in play. It's possibly due to the rise of people entering the hobby via watching televised 'actual play' by actors, or possibly a trend that's always been there but is just more visible now. A lot of people these days play D&D as if it was further right on the decisions/insertions scale. Players in a lot of games end up with a certain amount of creative control over the world.

To put it in fuzzier terms, they inject elements of a collaborative story-telling exercise into a relatively traddish TTRPG when they play. And that's fine. I suspect they might be better served by playing an actual story-telling game with design elements supporting that, but ultimately, let people have their own fun.

To sum up

This is just how I think about things. It's not a formal system or a position on how things ought to be done.

I think it's fair to say that all TTRPG involves the creation of story – and again, go read van Winkle's article for a really well-considered take – and that some people have the creation of that story as a more primary concern than others. I think that the phrase 'telling a story' has misleading implications when it comes to TTRPGs, which is why I personally avoid saying that TTRPGs deeply involve it, even if (getting into the weeds) it's true. And I find it interesting that when it comes to story, we can try to pin games onto two axes which quite often correlate with one another.